How Global Credit Oversaturation Affects Currency Markets

Credit is the fuel that drives economies. It helps governments fund projects, companies expand operations, and consumers buy homes or cars. But too much of it creates distortions. When credit saturates the global system, risks spill into currency markets. Exchange rates start reflecting not just trade balances or inflation, but also excessive borrowing and leverage. This pressure can push currencies down, trigger volatility, and in extreme cases, set off financial crises. Looking at how credit oversaturation interacts with currencies reveals why borrowing is never a free resource, even when lenders make it seem limitless.

Credit As A Currency Driver

Currencies move based on supply and demand. When capital floods into an economy, the currency may strengthen temporarily, as foreign investors chase returns. But if the credit surge is built on excessive borrowing rather than real productivity, it leaves the currency vulnerable. Once doubts surface about repayment capacity, capital can exit quickly, sending the exchange rate lower. This cycle has repeated across emerging and developed markets alike. Cheap credit creates artificial strength, followed by weakness when repayment risks rise. It’s this fragility that links oversaturation in global lending to turbulence in currency markets.

The Link Between Borrowing And Exchange Rates

Heavy borrowing expands money supply domestically, which can weaken the local currency against peers. Global investors watch these shifts closely, often punishing economies that show signs of unsustainable debt growth. Credit oversaturation can, therefore, reshape currency trajectories beyond what fundamentals alone would suggest.

When Oversaturation Becomes A Risk

Not all credit growth is bad. Economies need borrowing for development and consumption. Problems emerge when credit expands faster than output. If GDP growth slows while credit keeps rising, currencies face structural pressure. Investors recognize the imbalance and demand higher returns to compensate, driving bond yields up and weakening exchange rates. At the same time, oversaturation fuels inflation by pumping excess money into circulation, another downward force on currencies. In open markets, traders respond quickly, shifting funds into safer currencies like the U.S. dollar or Swiss franc. For oversaturated economies, this can mean sudden and painful devaluation.

Examples Of The Pattern

Latin American economies in the 1980s, Southeast Asia in the late 1990s, and even parts of Europe after 2008 all illustrate how easy credit leads to instability. Currencies initially appear strong during borrowing booms but collapse once the weight of debt becomes clear.

The Spillover Into Global Trade

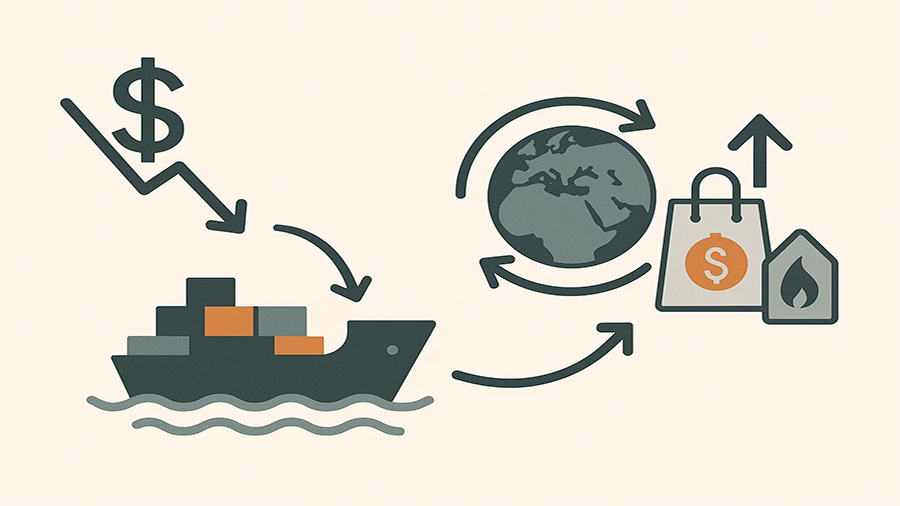

Currency moves driven by credit conditions affect trade. A weaker local currency can make exports more competitive, but it also makes imports costlier. For countries dependent on imported goods, oversaturation-fueled devaluation quickly feeds into consumer prices. This worsens inflation and undermines living standards. For global supply chains, it means shifting trade flows as buyers adjust to volatile exchange rates. Countries with stable currencies benefit, while oversaturated economies see reduced credibility. This feedback loop shows why global credit trends matter to currency markets, not just individual borrowers.

The Dollar As A Benchmark

Because so much global borrowing is denominated in dollars, oversaturation often strengthens the dollar itself. When other currencies weaken, demand for dollar assets rises, reinforcing its reserve status. The cycle leaves oversaturated borrowers doubly exposed, since they owe debt in a currency that grows stronger as their own weakens.

Credit Oversaturation And Currency Market Effects

| Stage Of Credit Cycle | Currency Impact | Market Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid credit growth | Temporary currency strength | Inflow of speculative capital |

| Debt exceeds productive growth | Currency begins weakening | Rising inflation and interest costs |

| Confidence erodes | Sharp devaluation | Capital flight, crisis risk |

The Role Of Central Banks

Central banks act as gatekeepers when oversaturation starts spilling into currencies. They can raise interest rates to defend the currency, but this also makes borrowing more expensive domestically, often pushing companies and households into distress. Alternatively, they may intervene directly in foreign exchange markets, using reserves to stabilize rates. Yet reserves are finite, and interventions can only buy time. When credit expansion has gone too far, even the strongest central banks struggle to maintain confidence. Currency depreciation becomes inevitable unless debt levels are brought under control. This tension explains why currency crises often coincide with credit bubbles bursting.

The Limits Of Intervention

History shows that interventions may delay volatility but rarely solve underlying credit problems. Markets eventually adjust, forcing devaluation if debt remains unsustainable. The credibility of central banks matters as much as their reserves.

Global Contagion Effects

Credit oversaturation in one region rarely stays isolated. When a major borrower struggles, global markets react. Investors pull funds from other countries perceived as risky, even if their fundamentals are stronger. This contagion spreads currency weakness across multiple economies. The Asian financial crisis of 1997 is a classic example: oversaturation in Thailand spread rapidly to Indonesia, Malaysia, and beyond. Today, with capital moving at the speed of digital markets, contagion risks are even higher. Oversaturation in one corner of the globe can ripple through currencies worldwide in days, not months.

Safe-Haven Flight

During contagion, investors shift into safe currencies like the dollar, yen, or Swiss franc. This strengthens those currencies further, while weaker ones spiral downward. Oversaturation amplifies the cycle, making crises sharper and recovery slower.

Implications For Borrowers And Policymakers

For governments, oversaturation highlights the need to balance credit expansion with sustainable growth. Borrowing for infrastructure or investment can support long-term productivity, but unchecked consumer or speculative credit adds fragility. For businesses and households, the lesson is similar: debt tied to stable income can be managed, but borrowing tied to speculation or short-term gains risks collapse when currencies weaken. Policymakers must monitor not just domestic credit levels but also how global oversaturation influences capital flows. In a tightly connected world, local lending booms quickly spill into exchange rates, inflation, and international trade competitiveness.

Preparing For The Next Cycle

Every credit cycle ends, but the severity of its impact on currencies depends on preparation. Strong institutions, diversified reserves, and transparent lending practices cushion the blow. Weak governance and opaque debt only magnify risks.

The Conclusion

Credit oversaturation is not just a banking issue—it’s a currency market risk. When borrowing outpaces real growth, currencies weaken, inflation rises, and crises become more likely. The short-term gains of cheap credit often give way to long-term instability, visible in sudden devaluations and capital flight. For economies plugged into global markets, oversaturation carries consequences far beyond borders. Whether it becomes a sign of crisis or a manageable part of modern finance depends on discipline: by borrowers, lenders, and policymakers. Without that balance, the flood of credit that once boosted growth can turn quickly into a force that erodes currency strength and global stability.

Daniel Reed is the founder and chief editor of MYA App. With more than 12 years of experience in finance, economics, and digital markets, Daniel brings a unique perspective to complex topics such as credit risks, global auctions, and investment strategies.

Daniel Reed is the founder and chief editor of MYA App. With more than 12 years of experience in finance, economics, and digital markets, Daniel brings a unique perspective to complex topics such as credit risks, global auctions, and investment strategies.